Click The Images To Go To Page Indicated A History of A.A. and Medicine The New "Cure" -- Off to a Shaky Start "The one valid thing in the book is the recognition of the seriousness of addiction to alcohol. Other than this [it] has no scientific interest." So scoffed the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in its Oct. 14, 1939, review of Alcoholics Anonymous, published the previous April. "It is in no sense a scientific book," the review continued, "although it is introduced by a letter from a physician [William D. Silkworth, M.D.] who claims to know some of the anonymous contributors who have been 'cured' of addiction to alcohol and have joined together in an organization which would save other addicts by a kind of religious conversion." Interestingly, the same issue of JAMA carried numerous ads for centers specializing in the cure of mental and nervous disorders, "general invalidism" and alcohol and drug addiction — few more prominently displayed than one touting the Charles B. Towns Hospital in Manhattan, where Dr. Silkworth had successfully treated A.A. cofounder Bill W. But, undaunted, the reviewer noted, "For many years the public was beguiled into believing that short courses of enforced abstinence and catharsis in 'institutes' and 'rest homes' would do the trick, and now that the failure of such temporizing has become common knowledge, a considerable number of other forms of quack treatment have sprung up. The book under review is a curious combination of organizing propaganda and religious exhortation." There were others who felt differently, however. The Christian Science Monitor, in its Aug. 17, 1939, edition, predicted, "The book Alcoholics Anonymous, on the subject of liquor addiction and its remedy, seems designed for a wide usefulness. … It has indeed been proved true … that something more than individual willpower — or 'won't' power — is necessary to heal what at least one special sanitarium recognizes in its advertising as a 'disease.'" And across the country medical practitioners were taking notice of reports that alcoholics long given up on by doctors were staying sober in the fledgling Fellowship. Bill and his A.A. co-founder Dr. Bob were quick to point out that the A.A. program of recovery was a synthesis of principles borrowed from the great religions, movements like the Oxford Group (a religious movement that was having some success with alcoholics), and medicine. Bill disarmed contentious members of the medical community when he acknowledged in an address before the New York Medical Society in 1944 that he couldn't explain exactly how A.A. works — then proceeded to intrigue them with stories showing it did work. One by one, as they saw their "hopeless" patients recovering in A.A., doctors became staunch advocates. Many, at risk to their professional reputations, would offer public support and even become integral parts of the Fellowship as Class A (nonalcoholic) trustees. Some started A.A. groups themselves when there was no one else to do so.

"Hopeless Inebriates" Alcoholics in the early 1900s were looked upon as "chronic drunkards," "hopeless inebriates," "pitiful creatures, sinners," and worse. But soon a handful of visionaries began to reshape the prism through which alcoholics were viewed by medical professionals and the public. In 1917, Charles B. Towns, Ph.D., who had founded a Manhattan hospital as a "drying-out" facility, wrote a groundbreaking article for The Modern Hospital magazine in which he asserted, "There is no such thing as 'curing' a case of alcoholism. There is nothing on earth you can do to prevent any human being from taking up the use of alcohol again if he wants to." In another article Towns wrote shortly afterward for Modern Hospital, he detailed the medical treatment given an alcoholic at Towns Hospital — basically a combination of barbiturates to sedate and belladonna to reduce stomach acids. Once the patient was medically stabilized, Towns advocated "physical conditioning" — a week or two of hydrotherapy, electricity and massage: "Get him 'into shape' physically, and you will then be able to get a definite line on both the physical and mental man." Decrying the concept of alcoholism as an inherited malady, Towns contended that "in many instances those about [the alcoholic] have been able to go back to the old family closet and haul out some alcoholic skeleton as the cause of his own drinking and as a 'horrible example.'" At the time he scoffed at the concept of alcoholism as a disease, but allowed that "a man who has a poisoned father, whose system is thoroughly saturated with 'booze'… could and probably would inherit a defective nervous system." Towns did emphasize that alcoholics "are poisoned patients.… they are sick." He was beginning to see the alcoholic's illness as more than one-dimensional. He believed that "lack of occupation is the greatest destroyer of men, whether the man be with means or without means, and you cannot expect to save either of these vagrant types… unless successful occupation has been found and responsibility in life has been created." In other words, Towns maintained, "you have not only got to treat a patient, but deal with a man!" A Sickness, Not a Stigma The passage of time only strengthened the view of the alcoholic as a sick, not morally defective individual, and would have far-reaching effects. Some 15 years later in his 1932 book Drug & Alcohol Sickness, Towns, whose approach to the treatment of alcoholism was constantly evolving, stressed that there is "no more disgrace in being treated for alcoholism than in being treated for pneumonia … "The man has been sick. And now he is well. That is all there is to it." A year later, in 1933, Bill W. entered Towns Hospital for the first time. Prohibition was winding down (it would be repealed in December 1933), and alcoholism was still viewed commonly as a mystery and a terrible shame. The prevailing view among physicians was that no matter what the treatment chronic alcoholics were doomed. For Bill, Towns was a revolving door that he would enter three times before he could stay dry. His attending physician William Duncan Silkworth, M.D., a specialist in neurology who had joined the staff in 1930, had already formulated his theory of alcoholism as an "allergy." But the treatment prescribed for the alcoholic at Towns had changed hardly at all. According to "Pass It On," a biography of Bill, "someone who remembered the hospital described it simply as a place where alcoholics were 'purged and puked.'" The purging likely resulted from liberal doses of castor oil the patients were given along with belladonna. Once Bill was better physically, Dr. Silkworth talked with him. The doctor described alcoholism not as a lack of willpower or a moral defect, but as a legitimate illness. It was his view, unique at the time, that alcoholism was the combination of a mysterious physical allergy and the compulsion to drink.

He broke down this concept into three phases of treatment that he outlined in a paper, "Reclamation of the Alcoholic," published in the April 21, 1937, issue of the Medical Record: "1. Management of the acute crisis; 2. Physical normalization and cell revitalization so that craving is eliminated; and 3. Mental and normal stabilization, which naturally involves some 'moral psychology.'" As a consequence of his close contact with alcoholics (and he saw thousands in his lifetime), Dr. Silkworth believed that "something more than human power is needed to produce the essential psychic change" vital to sustained sobriety. Nor did he "hold with those who believe that alcoholism is entirely a problem of mental control." For instance, he said, he had treated many men who had worked assiduously on an important business deal, only to have it fall apart because they picked up a drink. "Then the phenomenon of craving at once became paramount to all other interests. These men (by 1937 he would include women) were not drinking to escape; they were drinking to overcome a craving beyond their mental control." When the chips are down, Dr. Silkworth concluded, "the only relief we have to suggest is entire abstinence."

Rowland did get sober, with the help of A.A.'s forerunner, the Oxford Group (circa 1928-1939). An important feature of group life was the practice of confession, or "sharing." Members stood before audiences to tell about their failures in life and subsequent redemption. Then Rowland met another hopeless drunk, Edwin "Ebby" T., a childhood friend of Bill's who had stopped drinking with the help of the Oxford Group. Soon afterward a sober, glowing Ebby visited Bill, who by now had been through the Towns treatment regimen twice to no avail, and introduced him to the revolutionary idea that release from the bonds of alcoholism was possible through spiritual means. Almost eagerly Bill returned to Towns for the third time, and it was during this stay that he experienced his sudden and electrifying "spiritual awakening." Shaken, he confided in Dr. Silkworth, who responded gently, "Something has happened to you I don't understand. But you had better hang on to it. Anything is better than what had you only a couple of hours ago." Bill did hang on to it, stayed sober, and zealously went to work on other alcoholics, with no success at first. Dr. Silkworth straightened him out once again. "Stop preaching at them," he said, "and give them the hard medical facts first. This may soften them up at depth so they will be willing to do anything to get well. Then they may accept those spiritual ideas of yours, and even a Higher Power." Hearing the message from another alcoholic, Silkworth said, "maybe will crack those tough egos deep down." Several months later, while in Akron, Ohio, on a business trip in June 1935, Bill was seized by a powerful urge to drink; remembering Dr. Silkworth's words, he looked around for another alcoholic with whom he could share his experience, strength and hope. He connected with Dr. Bob, and the rest is A.A. history. "A Seething Caldron of Debate" Dr. Silkworth anticipated that prescribing total abstinence as an Rx for alcoholism would precipitate "a seething caldron of debate in the medical community" — which it did. Except for a smattering of A.A. supporters, most physicians were skeptical and still believed that alcoholics were a lost cause. As one doctor told some early members, "There is no doubt in my mind that you were 100 percent hopeless — apart from divine help. Had you offered yourselves as patients at this hospital, I would not have taken you. People like you are too heartbreaking." The new fellowship of Alcoholics Anonymous was not even five years old when Alcoholics Anonymous was published. "As our only medical friend at the time, the good doctor [Silkworth] boldly wrote the introduction to the Big Book," Bill later noted (Alcoholics Anonymous Comes of Age, p. 14). Dr. Silkworth put his reputation further on the line by contributing a chapter, "The Doctor's Opinion," which remains an integral part of A.A.'s basic text. Additionally, Bill said, Dr. Silkworth "helped to convert [Dr. Towns] into a great A.A. enthusiast and had encouraged him to loan $2,000" toward preparation of the book, a sum that was increased to $4,000 and later paid back in full. Dr. Towns also approached Fulton Oursler, then editor of Liberty magazine, who commissioned feature writer Morris Markey to write the article "Alcoholics and God" for the September 1939 issue, giving A.A. its first national publicity. It was publication of the pivotal article "Alcoholics Anonymous" in the March 1, 1941 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, however, that turned the tide for the Fellowship and catapulted its membership from 2,000 to 8,000 within a year. Writer Jack Alexander reported that numerous physicians were jumping on the A.A. bandwagon — among them 25 doctors in Chicago who were working hand-in-glove with A.A. and "referring their own patients to the group, which now numbers around 200." Dr. Foster Kennedy, A.A.'s first friend in neurology, asked several doctors, some outspoken in their endorsement of A.A., to discuss the program with his fellow neurologists at the New York Academy of Medicine. But they declined, saying, "in A.A. we see an unusual number of social and psychological forces working together on the alcoholic problem. Yet… we still cannot explain the speed of the results. A.A. does in weeks or months what should take years.… There is something at work in A.A. which we do not understand. We call this 'the X factor.'You people call it God. You can't explain God and neither can we — especially at the New York Academy of Medicine." (Alcoholics Anonymous Comes of Age, p. 46) With A.A.'s widening acceptance came invitations to speak at the meetings of several prestigious medical societies, and Bill seized the opportunities. Addressing a group of neurologists and psychiatrists at a May 1944 meeting of the New York Medical Society, he defused a possible me-against-you situation when he said, "You may inquire, 'Just how does A.A. work?' I cannot fully answer that question.… We can only tell you what we do and what seems, from our point of view, to happen to us." Borrowing from Dr. Silkworth, as he so often did, Bill described A.A. "as a synthetic concept -- a synthetic gadget, as it were, drawing upon the resources of medicine, psychiatry, religion amid our own experience of drinking and recovery. You will search in vain for a single new fundamental. We have merely streamlined old and proved principles of psychiatry and religion into such forms that the alcoholic will accept them." Bill underscored the roles of both medicine and religion in the A.A. program — pointing out, however, that "in one respect they do differ. Medicine says, 'Know yourself, be strong, and you will be able to face life.' Religion says, 'Know thyself, ask God for power, and you become truly free.'" In A.A., Bill said, newcomers may try either method and stay sober, but added: "If, however, the spiritual content of the Twelve Steps is actively denied, they can seldom stay dry." During a discussion period that followed, Dr. Kennedy commented on the "holy zeal" of A.A. members as they went about "Twelfth-Stepping" suffering alcoholics in order to stay sober themselves. "I think our profession must take appreciative cognizance of this great therapeutic weapon," Dr. Kennedy said. "If we do not do so, we shall stand convicted of emotional sterility and of having lost the faith that moves mountains, without which medicine can do little."

Dr. Monroe asserted that "the alcoholic is a sick person who needs help" and, "most important, can be salvaged." By the end of the first year, the number of patients discharged from this ward had reached 1,000, he reported. "On the basis of our experience, any other hospital undertaking a similar project in cooperation with Alcoholics Anonymous cannot fail financially, and the service rendered to the individual — and to the community — is incalculable." (By 1954, 10,000 alcoholics, referred by the New York Intergroup, had passed through Knickerbocker's alcoholic ward, "the majority on their way to freedom," Bill wrote in Alcoholics Anonymous Comes of Age (p. 206). Medical Affirmation

In presenting the award, the foundation noted that, "today this world fellowship of 4,000 groups, resident in 38 countries, is rehabilitating 25,000 additional persons yearly. In emphasizing alcoholism as an illness, the social stigma associated with this condition is being blotted out." It further lauded A.A. for working "on the novel principle that a recovered alcoholic can reach and treat a fellow sufferer as no one else can" and, "in so doing, maintain his own sobriety." History may recognize A.A. as "a great venture in social pioneering that forged a new instrument for social action; a new therapy based on the kinship of common suffering; one having a vast potential for the myriad other ills of mankind." Treating Body and Soul

But "A.A. can never be just a miracle," Dr. Tieboat reminded his audience. "The single act of surrender can produce sobriety by its stopping effect upon the ego," but, "unfortunately, that ego will return unless the individual learns to accept a disciplined way of life." A.A.'s friends in medicine almost unanimously agreed that the Fellowship was "not just a miracle but a way of life which is filled with eternal value," as Dr. Tieboat put it in his presentation at A.A.'s St. Louis convention. Within the confines of their unanimity was ample room for dialogue on the whys and wherefores of alcoholism. Dr. Bauer, for instance, spoke of alcoholism as an "escape… from intolerable situations" in life. Yet in an April 1962 letter to family member Helen Brown, Bill reflected on a thought Dr. Jung had expressed in a personal letter penned just months before his death. "[Dr. Jung] portrays the drinker as one who is seeking a spiritual release through alcohol," Bill related. "The good doctor was deeply convinced that this is part of the motivation that most heavy drinkers have. Therefore alcohol is not always taken for escape or obliteration — rather it is an attempt, very often at least, to reach higher values." Another longtime friend, author Aldous Huxley, "holds to this identical view," Bill noted. "And my own experience and observations tell me very much the same thing. But, alas, alcohol is a poison. A poison that eventually destroys us, despite our attempt to reach out through it.… There is no doubt, either, that alcoholism has its biochemical aspect. Dr. Silkworth, my physician of years ago, always felt this was true. For short, he called this unknown condition an 'allergy' and this term we use in A.A. literature." Dr. Silkworth's view that the action of alcohol on chronic alcoholics "is a manifestation of an allergy — in other words, a sickness of the emotions, coupled with a sickness of the body — has held through the years. As has his observation that something more than human power is needed to produce the essential psychic change." A Cooperative Venture As A.A. continued to expand not only in the United States and Canada but around the world, members of the medical community increasingly embraced and supported the Fellowship as they came to know firsthand what Bill had told them long ago: that nobody had "invented" A.A. and, furthermore, he couldn't explain exactly how it works, but it does. Rarely did Bill articulate A.A.'s debt to our friends more clearly than when he told a meeting of the Medical Society in 1958 that A.A. "once stood in a No-Man's Land between medicine and religion.… Over the years "there has been a great change in this respect. Clerics of every denomination declare that while A.A. contains no shred of dogma, it has an impeccable spiritual base.… You gentlemen of medicine also observe that A.A. is psychiatrically sound as far as it goes, and that it refers all bodily ills of its membership to your profession." Therefore, Bill concluded, "it is now clear that [A.A.] is a synthetic construct which draws upon these sources, namely: medical science, religion and its own peculiar experience. So menacing is the growing specter of alcoholism that nothing short of the total resources of society can hope to vanquish [it]." "When our combined understanding and knowledge have been fully massed and applied, we of A.A. know that we shall find our friends of medicine in the very front rank — just where so many of you are already standing today."

Index of AA History Pages on Barefoot's Domain As in so many things, especially with we alcoholics, our History is our Greatest Asset!.. We each arrived at the doors of AA with an intensive and lengthy "History of Things That Do Not Work" .. Today, In AA and In Recovery, Our History has added an intensive and lengthy "History of Things That DO Work!!" and We will not regret the past nor wish to shut the door on it!!

KEEP COMING BACK!

On the Web December 2006 in the Spirit of Cooperation Three mighty important things, Pardn'r, LOVE And PEACE and SOBRIETY |

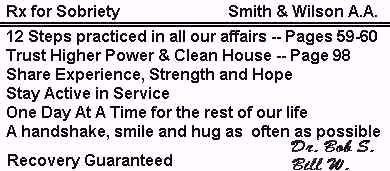

This advertisement for the facility where A.A. cofounder Bill W. received treatment ran in the same issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association as a review panning the newly published Big Book.

This advertisement for the facility where A.A. cofounder Bill W. received treatment ran in the same issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association as a review panning the newly published Big Book.